If you’re writing a PhD thesis, your reference list could be longer than an entire journal article.

Taming that monster can be tedious, but it’s worth taking the time to get it right.

A reference list that looks cared for tells your reader that you’ve paid attention to detail in your research. If everything’s where it should be – from the entries themselves to the full stops and commas – it will build trust in what you’re saying in the main text.

It’s kind to your reader to make sure they can easily find the full information on the sources you’ve cited.

If you’re having your work proofread, the more accurate and consistent your reference list is to begin with, the better the final version will be.

Here are six tips for creating and checking a reference list that will make you, your examiner and your proofreader feel … well … a bit better. Choose a day when you feel like doing a mechanical task, put the kettle on and break open a box of chocolates.

A quick note:

This post is about the author–date referencing system, also known as Harvard. I’ll be writing separate posts about other systems.

1. Follow your university’s guidance

There are many different versions of the author–date referencing system – including Harvard, APA (created by the American Psychological Association) and CSE (created by the Council of Science Editors). Some universities ask students to follow one (or any) of these variants, while others have their own author–date style and their own guidance.

Author–date referencing styles follow the same main principles, ordering the references by author surname and then by year of publication.

But they differ on style points, such as capitalisation, punctuation and italics (for more on this, see tip 4).

Different departments in the same university might use different referencing systems, so make sure you’re following the right one. Ask your supervisor for a copy.

If you send your thesis to a proofreader, send them a copy too so they can check any inconsistencies.

2. Include all the details.

I’ve noticed that the following details are often missing from references:

- Place of publication (for books)

- Edition number (for books)

- Journal issue number

- Page numbers (for journal articles and chapters in an edited book)

- Editors’ names (for chapters in an edited book and conference proceedings)

- Dates and venues (for conference papers and proceedings)

- Details other than a URL (for online sources).

Look at your guidelines to find out what details you need to include for online sources. For example, the details needed for a web page are usually different from those needed for a document that you accessed in PDF format, such as a journal article, report or PhD thesis. Many referencing guides advise you to reference PDFs of these documents in the same way you would reference a hard copy.

Make sure you’ve included everything you need to for online-only journal articles, online newspaper articles, blogs, and so on.

3. Order the references consistently.

In Harvard referencing, the entries in the reference list are ordered alphabetically by the author’s surname (or the first author’s surname, if there’s more than one author).

To reference more than one source by the same author (or authors), order them chronologically by the year of publication.

Then it gets a bit more complicated.

If you have more than one source by the same author (or authors) published in the same year, add a letter to the date to make clear which source you are referring to in your citations (for example, 2017a and 2017b). Use the same letters after the date in the references. The Anglia Ruskin University website gives examples.

When there’s more than one reference by the same lead author and different co-authors, order them consistently and in line with your guidelines. For example, you can order the entries alphabetically by the surname of the second (or third, or fourth, if needed) co-author, no matter how many authors there are. Or your university’s style might be to list all the entries with two authors first, then those with three authors, and so on.

If there is no guidance on this, choose a system and stick to it. The most important thing is to be consistent.

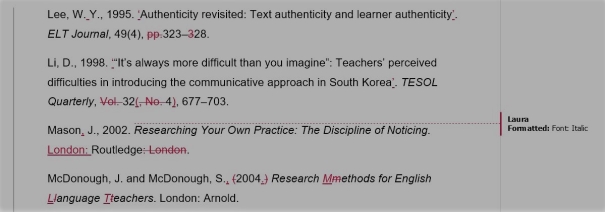

4. Check the style is consistent.

Here are some of the most common style points to look out for.

Tip: You’re more likely to spot inconsistencies if you:

- read through separately for each of the points mentioned below, and

- check different types of references at the same time (for example, all the conference proceedings, and all the chapters in an edited book).

Order of information

For each type of reference, make sure you’ve set out the information in the same order.

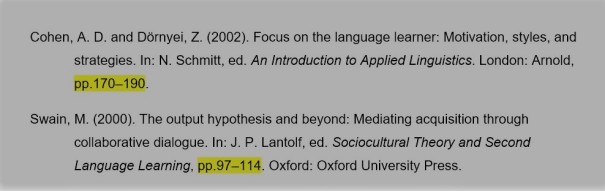

For example, in references to chapters in an edited book, have you always put the page numbers in the same place?

Punctuation

Check the punctuation your university’s referencing guide uses to separate the different information in the reference. When are commas, colons and full stops used?

Does your university put the date of publication in brackets? What about brackets around edition numbers and journal issue numbers?

Does it add full stops after authors’ initials? What about after abbreviations, such as ‘Ed.’, and after a DOI or URL?

Should you enclose article titles in quotation marks? If yes, should you use double (“Article title”) or single (‘Article title’)?

Should you separate numbers in page ranges with a hyphen (118-32) or the slightly longer en-dash (118–32)?

Tip: When looking at page numbers, check that they make sense. For example, the range 119–112 would ring alarm bells, as the second page number is lower than the first.

Capitals

Does your university’s reference style capitalise book titles and journal articles? What about titles of other sources, such as reports?

When a title has a colon in it, does your university capitalise the first word that follows the colon?

Should you capitalise abbreviations, such as ‘Vol.’ and ‘Ed.’?

Italics

Book, journal, magazine and newspaper titles are usually (but not always) italicised. What about other titles, such as reports, blogs and conferences?

Does your university’s style italicise ‘et al.’? What about journal volume and issue numbers?

Abbreviations

Does the referencing style abbreviate journal names or spell them out in full?

Does it include the abbreviation ‘pp.’ before page ranges or not?

Does it use ‘&’ or ‘and’ in the list of authors’ and editors’ names?

Does it abbreviate words like ‘translated’ (trans.), ‘edited’ (ed.) and ‘volume’ (vol.)?

Web links: URLs and DOIs

A URL is the address of a web page or other online content. A DOI (digital object identifier) is a string of letters and numbers that provides a permanent link to the online content (for example, a journal article). Many university referencing guides ask students to use DOIs whenever they can, because the link is permanent.

Check formatting – do you need to remove or keep the hyperlink in a URL?

Check it works – have you tested each URL and DOI? Does it take you to the right place?

Keeping the style consistent.

5. Make sure everything you’ve cited is included in the reference list.

It’s easy to forget to include a citation in the reference list when you’re writing such a huge document.

Having a proofreader pick up on any missing references is useful, but you’ll miss out on having those missing references proofread. That means it’s worth checking this yourself first.

If you’re not using reference-management software, there’s no quick way to do this.

Skim through the document looking for citations and check them against the reference list. Make a note of those you’ve found so you don’t have to check the same citation more than once.

You can do this on paper (for example, by skimming through and highlighting each citation) or on screen (using the ‘Find’ tool in Word to search for an opening bracket can be helpful).

Tips:

Save a copy of the reference list in a separate file so you don’t have to keep scrolling to the end of your document. You can then highlight the ones you’ve already found.

Everything in the reference list needs to be cited in the main text too, so look out for any entries that you haven’t found a citation for.

6. Check the references and citations match.

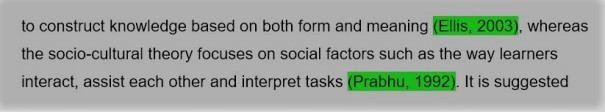

Each citation should link clearly to its entry in the reference list, without any confusion.

Check for the following inconsistencies:

- Dates not matching (for example, the citation says 1978 and the entry in the reference list says 1987)

- No date listed in the citation

- Missing accents in author names (for example, Dörnyei vs Dornyei)

- Missing letters in author names (for example, Philips vs Phillips)

- Authors’ names given the wrong way round (for example, the citation says ‘Rodgers and Brown, 2002’ but the entry in the reference list says ‘Brown, D. J. and Rodgers, T. S., 2002’)

- A website, newspaper or organisation name given in the citation but an individual author’s name given in the reference list (for example, the citation says The Times but the reference entry says Smith, A.).

How can a proofreader help?

For an assessed piece of work like a PhD thesis, a proofreader has to be careful about how much help they provide. Your work has to be considered to be your own, and that includes the reference list.

In the UK, guidance varies between universities but it is generally accepted that a proofreader shouldn’t create your reference list, apply a style to the references from scratch or look up missing information for you.

I correct one-off inconsistencies in style, but I highlight those that are more widespread for you to look at. I point out missing information, but I don’t add it for you.

For example, I’ll correct the capitalisation of a journal article if you have capitalised all your other journal articles. But if some are capitalised and others aren’t, I’ll highlight this so you can correct it.

Useful resources

Your university

- Your university should provide guidance on the exact referencing style they want you to use, whether they have their own or follow an external style. Some might not specify which you should use, as long as you’re consistent.

- For help, try the library or your university’s academic writing support service. They might also have a study skills support service.

Websites

- The Anglia Ruskin University guide is user-friendly, available for anyone to access and provides examples of a wide range of reference types.

- For APA style, the Purdue OWL has examples of many different types of references. There’s also the APA style blog, which is great for finding answers to tricky questions. The main APA website has an online tutorial.

- For CSE, you can subscribe to the Scientific Style and Format website. A quick guide is also available to non-subscribers.

Books

- Cite Them Right: The Essential Referencing Guide by Graham Shields and Richard Pears (paperback, Palgrave, 10th edition, 2016). Provides detailed examples of a wide range of reference types, using Harvard (and its variants) and other referencing systems (such as Vancouver, MHRA and OSCOLA). There are also resources available online.

- Concise Rules of APA Style by the American Psychological Association (spiral bound, APA, 6th edition, 2009). An easy-to-use pocket guide that contains detailed examples of reference types in addition to the rules on APA writing style.

- Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers by Council of Science Editors (Hardcover, University of Chicago Press, 8th edition, 2014). Chapter 29 gives specific guidance on references.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Mark Lawrence for giving me permission to use snapshots from his master’s dissertation. I have introduced inconsistencies to illustrate the examples given in this post.

Comment